8 Fascia Facts Every Yoga Beginner Needs to Know

- Joy Zazzera

- Feb 4, 2024

- 5 min read

Updated: Aug 23

Distinctions on Stretching, Stiffness, Why Hydration Isn’t What You Think and Why Fascia Matters in Yoga Anatomy

If you’ve been told your fascia is “tight,” “dehydrated,” or full of “fuzz,” it’s time for some clarity. Fascia isn’t just a trendy buzzword—it’s a foundational tissue system that plays a vital role in how we move, feel, stretch, and heal. But many common beliefs about fascia are outdated or oversimplified.

As a yoga teacher and massage therapist who lives with joint replacements, scar tissue, and decades of movement study, I approach fascia with both science and lived experience. Let’s walk through what fascia really is, what it’s not, and how you can work with it more intelligently—especially if you’re dealing with stiffness, injury recovery, or mobility challenges.

1. Understanding fascia: what every yoga student should know

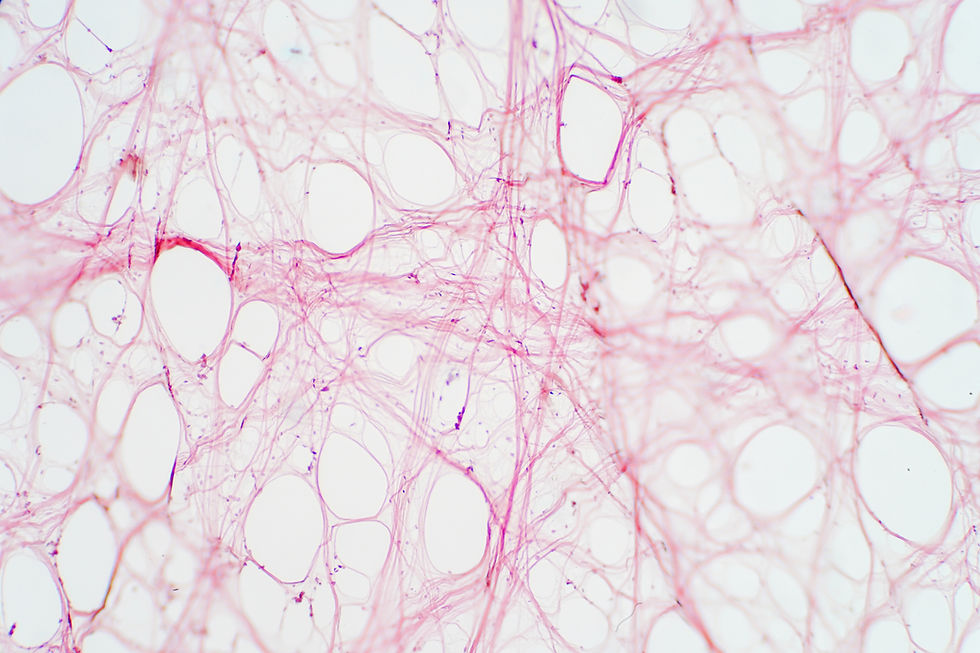

Fascia is a form of connective tissue that wraps, supports, and weaves through every part of your body. It’s not just one thing—it’s made up of several key components:

Collagen (primarily Type I) gives it strength and structure

Ground substance, a gel-like matrix, helps with nutrient exchange and hydration

Fibroblasts, the most common cell of fascia, help produce and remodel it

Elastic and reticular fibers add flexibility and support

Fascia isn’t just a “wrapping.” It influences the way your tissues slide, move, and recover. There are different types (areolar, reticular, dense regular, and dense irregular), each with specific roles depending on their structure and location in the body.

There are four types of fascia: areolar, reticular, dense regular and dense irregular. Fascia can be classified by depth (superficial, visceral or deep), fiber organization, function and location. in the body. For the purposes of this blog, I'll focus on areolar, the most abundant form of connective tissue in the body.

Areolar fascia is found everywhere you can find epithelial tissue: the digestive, urinary and respiratory systems, between muscles, organs, nerves and blood vessels that need to move. It's organization is comprised of a loosely dispersed cells and fibers, the most ground substance and elastin fibers of any type of fascia - making it the most mobile - and mast cells for immunity.

2. Fascia and Flexibility: What’s Really Limiting Your Movement

When we think about stretching, we often blame “tight muscles” or “tight fascia” for limited range of motion. But the first barrier to flexibility is often neurological, not structural.

The nervous system regulates how far we can safely go. Only after we pass that limit do we meet the resistance of our actual connective tissue. Areolar fascia, for example, is designed to help layers of tissue glide past each other. Dense fascia, like in ligaments and tendons, is more about stability than stretch.

That’s why passive static stretching, especially when done slowly and mindfully, remains one of the most powerful tools for improving flexibility. It influences both the nervous system and fascia—especially when we add time under tension (more on that soon).

3. Morning Stiffness, “Fuzz,” and Adhesions: What’s the Difference?

You may have heard of “fuzz” from Gil Hedley’s cadaver explorations. Some people now blame this fuzz for morning stiffness or tightness. But let’s clarify:

“Fuzz” refers to loose connective tissue that accumulates between surfaces at rest.

Morning stiffness is usually neurological—short-term adaptation after 6–8 hours of immobility, not fuzz buildup.

Adhesions are actual collagen bridges that form between tissues. They’re deeper, more structural, and form due to immobility, inflammation, or injury.

So if you feel stiff in the morning, it’s not likely “fuzz” gluing your muscles together—it’s more about your nervous system recalibrating after sleep.

4. Adhesions and Scars: What Forms Them—And What Might Help

Adhesions develop when collagen is deposited between tissues that aren’t meant to be stuck together—like muscle layers, fascia, or organs. They can form:

After surgery (scar tissue)

During long periods of immobility

As a response to infection, inflammation, or injury

Over time, blood vessels may infiltrate these disorganized collagen fibers, further complicating recovery. Some adhesions are harmless. Others can:

Restrict movement

Tether nerves and create pain

Alter organ or muscle function depending on location

Scar tissue, by contrast, stays within one tissue and tends to be less vascular. Both can affect mobility, but they respond differently to treatment. Neither is likely to be released with a foam roller alone.

5. Manual Release and Time Under Tension: What Really Works

Not all manual release is the same.

Sinking pressure (like in foam rolling) helps calm the nervous system and improve circulation

Cross-fiber friction and pin-and-stretch techniques can influence tissue organization more deeply

Prolonged, sustained stretching (especially in styles like Yin yoga) is key for affecting fascia at the intermolecular level

Time matters. Quick stretches rarely impact fascia meaningfully. To reorganize collagen fibers—especially in areolar CT—you need minutes, not seconds.

This doesn’t mean pushing through pain. It means creating a consistent, calm, and prolonged load that gives the tissue time to adapt and the nervous system time to down-regulate.

6. The Hydration Myth: Can You Really Hydrate Your Fascia?

The idea that we can “hydrate fascia” by drinking water is a misunderstanding of how fascia actually works.

Yes, fascia contains fluid—especially in the ground substance. But that water isn’t just sloshing around. It’s held in place by hydrophilic molecules like glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), which attract water through their electrical charge.

So what actually helps?

Movement is what stimulates circulation and fluid exchange.

Healthy fascia depends more on the presence of the right molecules (like hyaluronic acid) than on the volume of water consumed.

Sub-clinical dehydration is hard to define and varies widely. Unless someone is medically dehydrated, fascia stiffness is likely due to structural reorganization—not dryness.

7. Fascia and Aging: Why You Might Feel Stiff (But Aren’t Drying Out)

As we age, we accumulate molecules called AGEs (Advanced Glycation End-products). These form when sugars bind with proteins in the tissue and can:

Make fascia more crystalline and rigid

Reduce elasticity

Contribute to the “stuck” feeling in tissues

But AGEs are very hydrophilic—meaning they pull in more water, not less. So older adults might actually have more hydration in their interstitial fascia, despite feeling stiffer. It’s not a water issue—it’s a structure and sensation issue.

8. How fascia supports mobility and resilience

If fascia doesn’t need “hydrating” by drinking more water, and if stiffness isn’t always about fuzz or age, what does help?

Move often. Regular, mindful movement helps maintain fascia’s adaptability.

Stretch slowly. Give your tissues time under tension to respond.

Support recovery. Breath, rest, and nervous system regulation are just as vital.

Explore manual therapies. But know what each technique actually does—and that foam rolling isn’t magic.

Stay nourished. Your connective tissue needs quality nutrients, not just water.

Final Thoughts

Fascia is fascinating—and complex. It’s not just about tightness or hydration. It’s about how your body organizes itself over time, in response to how you move, rest, and recover.

As someone who studies fascia deeply and lives in a body with joint replacements, I’ve seen firsthand how intelligent movement can restore mobility and ease—even in the face of scar tissue, stiffness, and pain.

If you’re curious about working with fascia in a way that’s science-informed, nervous system-sensitive, and completely customized to your body, my yoga therapeutics sessions can help. You don’t need to push harder—you just need the right tools, time, and guidance.

Let’s move smarter—together.

Comments